Skip to main content

Penn Humanities Forum Connections: The East Asian Heartland and its Bronze Age Connections

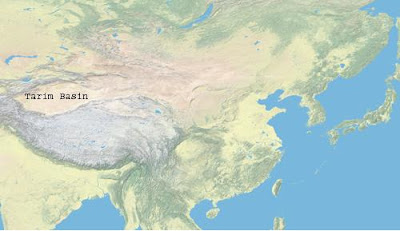

On Wednesday January 27th, Dr. Victor Mair, a Penn professor of Chinese Language and Literature lectured on The East Asian Heartland and its Bronze Age Connections as part of the series Penn Humanities Forum Connections lecture series. Dr. Mair highlighted the importance of the Tarim Basin in China’s northwest Xinjiang region and the substantial empirical evidence in art and ritual that shows China’s ties with the rest of the world.

Dr. Mair cited the Silk Road, the spread of Buddhism, and Alexander’s conquests of the East as common examples of China’s interactions with other empires. The Silk Road was established during the Han dynasty and began at the city of Xi’an, heading east through the Tarim basin and central Asia onwards to Persia, the Mediterranean, and Rome. Buddhist teachings came from India, and quickly spread not just to China proper but also to Korea and Japan. Alexander brought Greek and Macedonian culture right up to China’s western border. The Great Wall, built to keep out invaders from the steppes to the north and west, never succeeded. Evidence for these historical connections abounds in Chinese art and archeology. A comparison of the famous terracotta horses (shown at left) in the tomb of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, China’s first emperor, reveals a stunning likeness with horses in Roman statues. Felt alpine hats worn by peasants in south China look almost identical to those worn in Austria. Eye beads originating from Anatolia have been found throughout China. These artifacts exemplify China’s connections with the west. Symbols and rituals too connect China and the west. The Chinese symbol for shaman wu (巫) is derived from the Western heraldic symbol of magicians, the cross potent (below). Horses ritualistically killed and buried alongside an official in Shandong province steer us to Scythian rituals of the same type.

Dr. Mair cited the Silk Road, the spread of Buddhism, and Alexander’s conquests of the East as common examples of China’s interactions with other empires. The Silk Road was established during the Han dynasty and began at the city of Xi’an, heading east through the Tarim basin and central Asia onwards to Persia, the Mediterranean, and Rome. Buddhist teachings came from India, and quickly spread not just to China proper but also to Korea and Japan. Alexander brought Greek and Macedonian culture right up to China’s western border. The Great Wall, built to keep out invaders from the steppes to the north and west, never succeeded. Evidence for these historical connections abounds in Chinese art and archeology. A comparison of the famous terracotta horses (shown at left) in the tomb of Emperor Qin Shi Huang, China’s first emperor, reveals a stunning likeness with horses in Roman statues. Felt alpine hats worn by peasants in south China look almost identical to those worn in Austria. Eye beads originating from Anatolia have been found throughout China. These artifacts exemplify China’s connections with the west. Symbols and rituals too connect China and the west. The Chinese symbol for shaman wu (巫) is derived from the Western heraldic symbol of magicians, the cross potent (below). Horses ritualistically killed and buried alongside an official in Shandong province steer us to Scythian rituals of the same type.

China’s interactions with the West begin and end at the Tarim basin, China’s door to the western world. The basin contains a desert called Taklamakan, popularly accounted to mean “go in and you will never come out.” Starting from the 1980s, archeologists have found mummies in the desert with distinct Caucasian features, possibly indicating an ancient civilization existing in the crossroads between Asia and Europe. Dr. Mair heads a group that genetically mapped the mummies, and found that they had links to Europe, India, and Mesopotamia. Textiles found with the mummies were plaid, a Celtic pattern, and hats buried with the mummies also were of European design. These mummies demonstrate that the Han Chinese Empire even 3000 years ago had never been isolated from the rest of the world. Information, trade, and people have flowed between China and the west for millennia, a connection that no amount of Great Wall had ever been able to sever.

China’s interactions with the West begin and end at the Tarim basin, China’s door to the western world. The basin contains a desert called Taklamakan, popularly accounted to mean “go in and you will never come out.” Starting from the 1980s, archeologists have found mummies in the desert with distinct Caucasian features, possibly indicating an ancient civilization existing in the crossroads between Asia and Europe. Dr. Mair heads a group that genetically mapped the mummies, and found that they had links to Europe, India, and Mesopotamia. Textiles found with the mummies were plaid, a Celtic pattern, and hats buried with the mummies also were of European design. These mummies demonstrate that the Han Chinese Empire even 3000 years ago had never been isolated from the rest of the world. Information, trade, and people have flowed between China and the west for millennia, a connection that no amount of Great Wall had ever been able to sever.

Due to Dr. Mair’s distinguished work, these mummies will be opening at the Penn Museum on February 5th, 2011. Everybody is welcome to attend.

-- Rosie Li (CAS '11)

Comments

Post a Comment

We follow the House Rules as outlined by the BBC here.